December 12, 2025

Poston Pilgrimage 2025

A Travel Blog

I had the privilege of attending the Poston Pilgrimage with our director Leonard Chan last week, driving all the way from San Mateo to Parker, Arizona. This year marks 83 years since President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, an order that resulted in the movement of over 120,000 Japanese Americans into internment camps. Poston received the most internees, with over 18,000 people forcefully moved to the Colorado River Indian Tribes Reservation (CRIT).

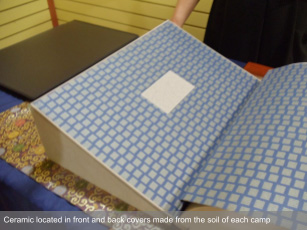

Our mission was to tour the camps and stamp the Ireichō, a project led by Professor Duncan Ryūken Williams of the University of Southern California. Leonard talked about the project with Prof. Williams back in 2022, and you can find the interview here. In summary, the book is a monument to console the names of the 125,000 people that were interned during World War II. The names are both listed in this massive book and online at their website, ireizo.org. Leonard and I used the website to discover the full name and birthday of Ben Denichiro Sanematsu, an author whose book AACP published in 1998.

I figured I would write our journey in a travel blog style; I’m really reminiscing about blogs from the early 2000s. I owe this to my great aunt’s 2010 Sony Cybershot Digital Camera.

Thursday, October 23, 2025

We had everything finalized and packed around noon, and Leonard wore a Giants hat so that people would know we were from the Bay. We didn’t forget to stop at Takahashi Market to grab some lunch before heading down 101 South.

Going south, we went through Gilroy and drove past the San Luis Reservoir. If I’m being honest, I haven’t had the chance to explore enough of California — apologies to Leonard on behalf of my expressions of awe and bewilderment. The land was vast and empty, aside from the farmland and rolling plains. Thank you for taking photos while I drove!

We approached the western portion of the Mojave Desert where Leonard pointed out that we were passing by Edwards Airforce Base. Eventually, we made it to Barstow, CA close to 8 pm.

Friday, October 24, 2025

The next day, we continued to drive further into the desert. You can tell how old the land is by observing the sediment layers in the mountains; did you know that the Mojave Desert’s oldest rocks are dated to be 1.7-2.5 billion years old? Sadly, we did not see Snoopy’s brother, Spike, while passing through Needles, Arizona.

As we drove down Needles Freeway (I-40), the temperature continued to creep into the 80’s. We also stopped by Lake Havasu and took a brief break at the London Bridge. It has actual bricks from the old London Bridge in the UK! Built to help with tourism for this originally-small town, the bridge connects the mainland to its island with more residents and restaurants.

This was about 45 minutes away from Parker, but it was a beautiful drive that followed the Colorado River and mountain peaks.

Soon enough, we arrived at Parker, unpacked the books, and ran to the CRIT Museum. No pictures were allowed inside the museum besides the Ireichō. Professor Susan Kamei and researcher Karen Kano led the orientation when we arrived, telling us more about the Irei Project, the book’s journey, and the symbolism of stamping names in the book. Although thousands of names have been stamped, 40,000 names are still missing a Japanese hanko (stamp). The Ireizō website states:

The idea of a book as a monument is inspired by the Japanese tradition of Kakochō (literally, “The Book of the Past”), a book of names typically placed on a Buddhist temple altar and brought out for memorial services when the names of those to be remembered are chanted.

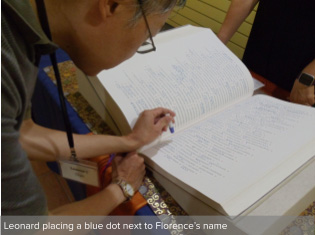

It was an honor to place a blue dot next to AACP’s founder’s name, Florence, and her husband, Mas (key member of AACP). We wouldn’t have even been in Arizona without their mission. Stamps were also placed next to Jack Shigeru Matsuoka, Hiroshi Kashiwagi, and, as I mentioned earlier, Ben Denichiro Sanematsu, all authors whose books have been published by AACP.

Matsuoka wrote Poston Camp II, Block 211, a series of cartoons about life in the camp. Kashiwagi released his memoir Swimming in the American and a poetry book Ocean Beach. Our director Leonard has an interview with him that I will include here.

Sanematsu’s autobiography Inward Light details his life, being moved to Poston, and becoming a teacher as his blindness progressed.

The leaders of the project are ensuring that every person stamps a name that has yet to be stamped by their family/descendants, so I was also able to stamp Hagemu Ono while Leonard stamped for Toru Nakamura.

Saturday, October 25, 2025

The next day, we returned to the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) Museum. It is a small, but knowledge-filled museum that features artwork such as beading, clothes, and ceramics from local tribes. The CRIT comprises the Mohave, Chemehuevi, Hopi, and Navajo. The Mohave and Chemehuevi have resided on the land for centuries, but the Hopi and Navajo were moved to the area in 1945.

We were provided with introductions by CRIT Royalty, and the Ase S’maav Parker Boys and the River Tribes United Dance Group sang and danced, inviting Pilgrimage attendees to join. Prof. Duncan Williams then performed a ceremony alongside attendees who recited the names of everyone that died at Poston.

CRIT Youth were invited to stamp the Ireichō to bridge the history of the two communities. Both groups have been subjected to cruelty at the hands of the U.S. government — this gesture was incredibly moving. We learned about Camp Poston from the tribe’s perspective; chairwoman Amelia Flores spoke about the reality of the CRIT. Japanese Americans were brought to the land, held there, and released, but the CRIT remained. The “reservation is home” and has been home to the tribes for thousands of years; despite this being their land, the area lacks ample labor force, funding, water sovereignty, and transportation. The CRIT Museum also had a display shedding light on the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) movement.

Afterwards, we drove to the Poston Memorial Monument. It was built in 1992, in memory of those that were herded and removed to the camp. I had the honor of talking to Sus Ikeda, a camp survivor that was brought to Poston, Block 16, when he was just 17 years old. His dad had first been taken by the FBI, leaving him to help his mother care for his five siblings. Sus said his first memory was stepping onto the ground, aghast at the 115º heat. He noted that the weather change from Salinas to Poston was unbelievable.

“We’d go swimming in the canals just to cool off. That was a real relief. And twice a month, we’d get a windstorm and just sit in the barracks, watching outside.”

As we stood there, two families overheard that he was from Block 16, inquiring if he’d known their families, Inoshita and Shinogawa. He said that the names seemed familiar, joking that at the age of 100, his memory is not entirely what it used to be.

When asked how he felt–if he had been angry, sad, in disbelief–he said, “You know the word gaman in Japanese, to endure, [laughs]. It was something that was beyond our control. We had to make the best of the situation.” His assigned job was delivering ice and helping to build the camps. Later on, he was asked to join the army, but was not physically qualified until being drafted again for the Korean War. Sus was very sharp and friendly, and he has remained in San Jose since leaving Poston.

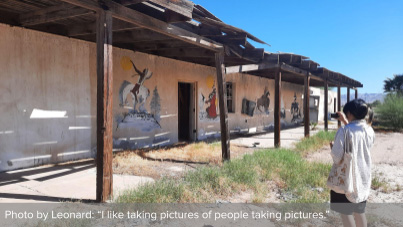

From the Memorial, we went down the street to the school buildings, all designed by the Japanese Americans brought here. It was difficult to imagine them being made completely by hand in the dry heat that blankets the valley.

Once internees were allowed to leave camp (fall 1945), land was turned over to the CRIT. These buildings were repurposed by the community and eventually abandoned, left in a state of disrepair.

Artwork left behind illustrated “the Red Road to Sobriety”, mourning those in the Indigenous community that have struggled with substance abuse. The Red Road is an organization that is fighting for addiction awareness and prevention. They cite that the “legacy of trauma, as well as the social isolation, poverty, education, high incarceration rates, and inadequate access to health care on reservations are all root factors of substance abuse” among Indigenous people (The Red Road).

Across this land were continuous reminders of both Camp Poston and the lasting effects of colonization. While standing here, I reflected on the injustices that continue to plague the country today; they are inescapable, even in the forgotten corners of the U.S.

We attended lunch at La Pera Elementary School, followed by two workshops of our choice. Our first workshop was a film screening of The Blue Jay by Marlene Shigekawa, president of the Poston Community Alliance (PCA). The film focuses on the relationship between internees and the existing tribal community; a young couple bonds with an Indigenous officer, exchanging a hand-carved bird lapel for baby formula. The cruelty of the camp is exemplified by food supply sabotage, an internee’s death, and constant surveillance.

Marlene’s presentation “Poston Live” is an educational program that PCA plans to introduce to schools and universities. We learned about the details of the “Indian New Deal” reforms started by John Collier, Commissioner for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The BIA wanted to preserve Natives’ cultures and maintain the lands, and they hoped to achieve this by repopulating the area and developing their agriculture. While assembling the internment camps, the government ensured that successful Japanese farmers were sent to Poston to support the local economy. They erected the irrigation system that is still used to this day, although this system was originally rejected by the CRIT. Either their land would be taken by white farmers or remain under governmental jurisdiction. The Blue Jay demonstrates the tension between two communities whose humanities lie in the government’s hands.

After this, we had the opportunity to attend “Arts, Crafts, and Photography” by Christina Hiromi Hobbs. Their presentation showed a wide array of art created by internees, ranging from photography to shell crafts and bird carving school. Bird carving became increasingly popular, as evidenced by bird carving membership cards and a Poston newspaper article announcing additional classes to “meet the demand of the students.” One of the other attendees brought their father’s bird collection, which was truly beautiful to look at.

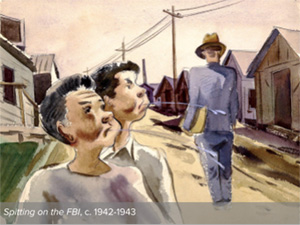

Notable artists such as Gene Sogioka, Kakunen Tsuruoka, and Isamu Noguchi were at Poston (although Noguchi was self-interned). Sogioka was originally a Disney artist and Tsuruoka was an Asian art dealer; these professions heavily influenced their work produced from inside the camp. Sogioka’s are active and dynamic, with other works including Six Pro Axis Commit Violence, Political Fires of Discontent, and Mr. Nosey Gives Marriage Counseling. These contrast significantly from Tsuruoka’s somber Chinese-inspired watercolor paintings like Desert Landscape and Industry in the Desert.

Christina emphasized that the art was not only a pastime, but also a form of resistance for internees. While this is clearly evidenced in Sogioka’s, more subtle details lie in the bird carvings’ feet made from the wires of the barrack houses.

On our way back to the hotel, Leonard and I stopped at the Memorial Monument again. The design is a hexagon base to mimic a Japanese stone lantern, and the spout at the top helps to angle water away from the plaques. Plaques provide the history of Poston and the names of those who voluntarily served in WWII to prove Japanese Americans’ loyalty to the U.S.

Standing here, amidst the quiet land and this large sundial, I silently sent a blessing to everyone that came before me. There is a separate, smaller post with plaques that provide poems published in the Poston Bungei while the camp was populated. A free verse by Yoshitake Morita reads:

Endless war

and endless desert

a line of simmering air.

The plaque next to it includes a declaration of the CRIT’s sovereignty along with their history. “The essence of the land exists in the hearts of the indigenous people.”

Looking out into the distance, I felt insignificant compared to the aging mountains and lingering history. I hope that this is not forgotten as our country continues to march backwards.

Spike image from Peanuts Comic Strip © by Charles M. Schulz

Spitting on the FBI © by Gene Sogioka

Poston After Sundown © by Kakunen Tsuruoka

Copyright © 2025 by AACP, Inc.