October 31, 2025

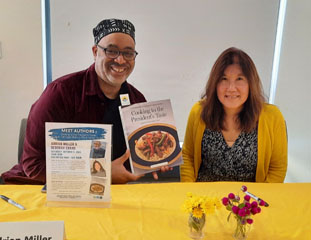

An Interview With Adrian Miller and Deborah Chang

Authors of

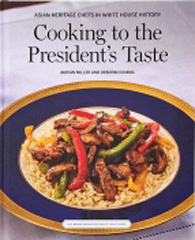

Asian Heritage Chefs in White House History:

Cooking to the President’s Taste

Interviewed by Christina Tai (CT) and Leonard Chan (LC)

CT/LC: Both of you have extensive backgrounds. You are both alumni of Stanford and were both lawyers. Adrian, you even had a period where you served in the Clinton administration at the White House. But you also both had an interest in food and cooking. Very briefly, tell us about your journey to writing this book. When did you first start to think about doing this book and how did you get interested in writing it? Specifically, tell us about Chef Lee Ping Quan. He seems to be the key to your book. Who was he and tell us about the book that he wrote? How did your backgrounds help you in writing this book?

Adrian Miller (AM): I became a food writer quite by accident. After working in the Clinton White House, I was actively trying to move back to my hometown of Denver, Colorado to continue my political career. The job market was slow, so I was in Washington, D.C. much longer than I expected. I fell into a dreadful pattern of watching a lot of daytime television. I’m embarrassed to admit the shows that I watched extensively. In the depth of my depravity, I said to myself, “I should read something.” I went to a local bookstore and Southern Food: At Home, On the Road, In History by John Egerton caught my eye. In that book was the following sentence that piqued my curiosity and changed my life: “[T]he comprehensive history of black achievement in American cookery still waits to be written.” The book was fourteen years old when I read it. I emailed Mr. Egerton, told him how much I loved his book, and asked if he still felt that his challenge was still true. He replied that it was only met in part, that there was room for additional voices, and why not mine. With his encouragement, I launched my food writing career.

While researching African American chefs in the extensive cookbook collection at the University of Denver’s Special Collections Department, I came across an extraordinary book published in 1939: To a President's Taste: Being the reminiscences and recipes of Lee Ping Quan, ex-president's steward on the presidential yacht, U.S.S. Mayflower, as told to Jim Miller. I nearly fell out of my chair. Part memoir, part cookbook, it was the most comprehensive book about a presidential chef up to that point. Quan served as the presidential yacht chef for Presidents Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. After his presidential cooking stint, he started several high-end restaurants in New York and Maine, but they all failed due to the Great Depression.

Deborah Chang (DC): I did an “odd”, non-traditional, career pivot in the early 2000s. I left a big law firm position and the law completely to try something new. It was the beginning of a lifelong journey of self-growth and learning. I decided on culinary school not because I hadn’t necessarily always wanted to be a chef, but because it seemed fun and I could learn some practical skills. If I had extensively researched what it was like to actually be a chef, I have to confess, I’m not sure I would have done it! Strangely, my lawyer and general “being a good student” skills like working hard, paying attention, asking questions, served me well in culinary school. I discovered that I like to learn new things, made life-long friendships and I was making delicious food at the same time!

So when Adrian and I happened to have dinner with a mutual friend of ours, the stars aligned as he was looking for someone to do the cooking part of the project.

LC: Did all the early AAPI chefs for the president start off as being in the military? Was that typical for even the non-AAPI chefs that cooked for presidents? Did their military experience help them in cooking in all sorts of tight spaces like ships and trains, which came in handy when cooking for presidents on their travels?

AM: Yes, based on the current data available, and they entered naval service. That’s how some end up cooking on the presidential yacht. African Americans, Latinos (a small number), and whites filled out the ranks of presidential cooks, but the overwhelming number of them were not military cooks. Their military experience certainly honed their cooking skills in a variety of culinary spaces, including airplanes, boats, and trains.

CT: In your book, you mentioned chefs who were hired through Service-by-Agreement (SBA), hired only for special functions. During your research have you seen a major difference in the career paths between the White House Executive Chefs and those of the Service-by-Agreement (SBA) staff chefs? If yes, why?

AM: There doesn't seem to be that much of a difference these days. Since the 1960s, most White House chefs, as well as the SBAs, have either upscale hotel and/or fine dining restaurant experience. Before that, presidential cooks were a mix of enslaved and free servants (of all races) , hired out caterers, cooks hired from the labor pool, and military cooks.

CT: There appeared to be a theme of culinary diplomacy of these trained AAPI chefs preparing elaborate meals for visiting diplomats and heads of state such as Chef Pedro Udo cooked for Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip of England. How involved were/are these chefs' in planning the menus of these events?

AM: It really varied upon how involved the First Lady was in the planning and the setting. The first step is to get a U.S. State Department briefing that detailed the dietary restrictions of the visiting dignitary. Then the chef proposed a series of menus that were then approved by the First Lady and sometimes the president. If the meal took place at the White House, the First Lady was more hands on about the menu details. Otherwise, the Air Force One, train, and yacht chefs had a great deal of latitude in what was served.

CT: In your book, I encountered a reflection of the chefs' experiences of what Asian Americans came across during their times in American History. What do you think of Lee Ping Quan's post presidential career as he was not able to have successful restaurants although he was a highly talented and acclaimed chef? Was race a factor?

AM: I don’t think race was a factor in Chef Quan’s unsuccessful restaurant career. He started his restaurant at a time when Chinese food was trendy. It’s just that the economic environment was too challenging. He offered upscale food during the Great Depression. In a February 20, 1938 article in The Atlanta Constitution newspaper noted, “People just didn’t seem to want to eat like presidents in those lean years, and restaurant after restaurant closed behind Quan.”

CT: I have not heard of the AAPI chefs mentioned in your book. How come not more of these chefs used their acclaim in the White House to further their culinary careers? During your research, have you encountered any of them pursuing being a celebrity chef after working for the President? Or did many of these chefs just retire after working for the President?

AM: Besides Quan, only Shiro Tsurusaki and Chef Ariel de Guzman tried to leverage their presidential cooking experience into something lucrative. Much like Quan, Tsurusaki opened a restaurant near Marlboro, Maryland in the early 1930s that featured presidential cuisine. He named it the “Mayflower House” as a nod to the presidential yacht on which he served. Newspaper advertisements touted that he served on the U.S.S. Mayflower for twenty-five years and cooked for six different presidents. After presidential cooking career ended, Chef Ariel de Guzman published The Bush Family Cookbook in 2005. This cookbook relates Chef de Guzman’s experiences of cooking for President George H.W. Bush and First Lady Barbara Bush. Most of these chefs either went on to other naval assignments, got reassigned in the White House, or retired.

CT: What was your biggest surprise that you encountered while you researched the book?

AM: For me, it was the sheer number of Asian heritage chefs that have been involved in so many aspects of presidential foodways. There were so many, I don’t have an exact number, that we took the approach of profiling one or two cooks who represented a particular aspect of presidential cooking. Prior to writing this book, I thought African Americans clearly dominated the ranks of the people of color who have cooked for our nation’s First Families. I can no longer say that.

CT: I found the book a fun and fascinating journey of culinary diplomacy with historical storytelling enhanced with food. Deborah, you did extensive research and experimentation for the recipes. What challenges did you have in getting the recipes ready for the book? How did you decide which recipes got in? Who did you taste test the recipes with? What was your most surprising anecdotal story that you encountered in your research?

DC: There were over 400 recipes in the original book. The recipes were written very sparsely, with little instruction for the home cook. I imagine the actual process on his end being very time consuming, and I wonder to myself how it was done. I would guess that Chef Quan didn’t even have the recipes written down first, because if he did, he could have at least revised the organization of the recipes into categories, because even the categories were hard to discern. For example, he starts off with “Chinese Dishes,” then to “Vegetables,” “Meats,” “Appetizers,” “Sauces,” “Cakes and Cookies,” “Pies, Desserts, and Drinks,” “Entrees and Main Course for Light Luncheons,” and then he ends with long sections breaking out recipes by fruits like “Oranges,” “Bananas,” “Pineapple,” “Coconut,” mixing both savory and dessert dishes in those sections.

Very early on, I decided to do the best I could, that I wanted to include as many of Chef Quan’s Chinese dishes as were workable. Chef Quan started out with the Chinese recipes I found that meaningful. There were about 17 of them, including variations of each other, many of which were variations of “Chop Sueys.” The first recipe I tested, and I’m glad it ended up on the cover of the book, was Pepper Steak. Then I went through the rest of the recipes and included those dishes that people would eat today and conceivably be made at home – fried chicken, Chinese noodle dishes, steaks, muffins, cookies, soups – as opposed to dishes that required hard-to-source ingredients, combinations of food that don’t exist as much today, or extremely complicated dishes. Those included recipes like Boneless Goose, Banana Cocktail, and Green Turtle Soup.

With recipe writing, one question that I kept in mind throughout, was how much should I change the recipe? I wanted to be historically accurate to Chef Quan’s recipes, and not turn the recipes into mine. A very early decision I made was to keep the “Chop Suey” recipe title in the cookbook even though restaurants describe similar dishes as stir fries these days. With all of the recipes, whether it be the savory or dessert, or lunch or dinner, or Western or Chinese, I had to expand the instructions. This was relatively easy for both the Western and Chinese non-baking dishes. This became much harder for the baking dishes as baking requires accuracy. For example, “bake in a slow oven” could be baked in a 200, 250, 300, 325, 350 degree oven. Which one? Baking also requires technique as Chef Quan was not privy to the luxury of our small appliances, like electric mixers. A home cook mixing batter and egg whites by hand is different from someone with formal training. I found this out the hard way when I tested the pound cake, cookies and muffins at home.

This leads me to my favorite part of the project, and that was working with students from a high school for testing. I reconnected with my good friend who runs a culinary program at a high school in Sacramento. In California, high school students have to take a Career and Technical Education Credit, and some schools have culinary programs to fulfill this credit. So I would take the recipes to my friend and he’d have his students test them, and give feedback. They were amazing – earnest and diligent – and it was very fulfilling for me to see the recipes come to life in that way.

For the chefs other than Chef Quan – whom I’ll refer to as the Modern Chefs – the recipes were selected by them so I didn’t have to select any recipes. I didn’t make very many changes to them except break them out if there were many components – Chefs like to put many components into one plate – a protein on a starch – for example, would be two recipes.

CT/LC: What do you see for the future for AAPI chefs in the current administration which is so anti-ethnic everything (e.g. anti-DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion])? Is having AAPIs in the cooking staff seen as being too diversifying?

AM: Remarkably, President Trump has been quite happy with having Asian heritage chefs in charge of the White House Kitchen. Cristeta Comerford, a Filipina and the second longest tenured White House Executive Chef, served during the entirety of his first term. After Chef Cristeta’s retirement, Chef Permsin “Tommy” Kurpradit, the son of Thai immigrants, was promoted to the executive chef position in August 2024. He’s been in that position ever since.

CT: Do you think you would consider having a documentary inspired by the book, and why?

AM: Whether it be a documentary, an Academy Award-winning biopic, or a Tony Award-winning theater production, we’d LOVE to see these stories get told in other forms. We really want to share these stories with as many people as possible.

CT: What are your next pursuits after writing the book?

AM: We’re promoting the book across the country, and we’re happy to do in-person or virtual author events. In addition to that, I’m working on several projects: a book on leadership lessons from the White House Kitchen, a leadership team-building workshop on hosting a state dinner, and a multimedia project on African American street food vendors.

DC: I have found that I am a lifelong “learner” so I am working on different creative pursuits. I’ve also reached the stage in my life where I’d like to use my many professional skills to help others so exploring those opportunities as well.

LC: One last thing, you mentioned that you would like to share a recipe with our readers. Please tell us about it and why you chose to share this one. Is it a recipe that didn’t get in the book?

DC: I chose Masako Morishita’s Garlic Edamame Dumplings. I’m always impressed with executive chefs who are female, and she’s the executive chef of a very high-profile restaurant. This recipe is also currently on her menu at Perry’s. Plus – she’s multi-talented! She used to be an accomplished dancer and transitioned into cooking.

Garlic Edamame Dumplings

Chef Masako Morishita

.

Ingredients

Makes approximately 70 dumplings

.

● 1 lb shelled edamame

● 2-3 cloves of garlic

● 1 Tbsp salt

● 1/3 cup Extra Virgin Olive Oil

● 2 Tbsp soy sauce

● 2 Tbsp lemon juice

● 6 Tbsp mayonnaise

● Dumpling wrappers

● Small dish of water

.

To Garnish

● Extra Virgin Olive Oil

● lemon

● parmesan cheese

● black pepper

● chives, finely chopped

.

Directions

Combine edamame, garlic and salt in a blender or food processor until well mixed, then add olive oil, soy sauce and lemon juice. When everything has combined, add mayonnaise and blend again. Scrape the mixture into a bowl.

Hold a dumping wrapper on your palm and place about 1 tsp of the filling in the center of the wrapper. Dip a finger in the water and moisten the edge of the dumpling skin. Fold in half, then fold the edge of the dumplings like small waves using your fingers to seal.

Copyright © 2025 by AACP, Inc.